In a little cabin tucked away in the woods east of Holmes Harbor, rock stars are made.

Crammed with equipment and wailing musicians, it’s from this hideaway recording studio that a man known for his “big ears” and uncanny ability to perfect raw tunes has been helping bands make their way to stardom for nearly 20 years.

Business, as they say, is booming.

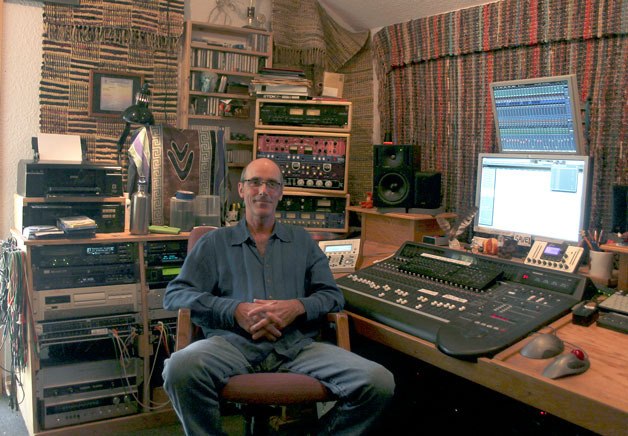

David Malony, owner of Blue Ewe Studios and drummer for South Whidbey’s very own Western Heroes, opened the studio in the mid-1990s. Hidden in the greenery behind his house, his sound laboratory has mastered digital music copies for island and Puget Sound area musicians alike. He’s said to have a knack for sound, and it has brought acts to the island for years.

“I call him ‘big ears,’” South Whidbey-based singer-songwriter and vocal coach Jana Szabo said. “His ear is so in tune with what I’m trying to get across. He’s always ahead of the bar with me, which is unusual.”

The recording is done in a 16-by-20-foot main room, but it’s the 18-foot ceiling that makes the sound work, Malony said. The main room is the original cabin structure, but Malony has added on multiple smaller isolation rooms. A cozy 10-by-10-foot vocal room allows singers to work their windpipes, and on the opposite side of the cabin is Malony’s 10-by-14-foot control room stocked with all his gadgets, control boards and his throne. All rooms have windows that peer into the main room, so all artists can look at each other while having their sound completely isolated. Natural light comes in from an atrium in the main room, the only reference to the outside world when musicians get lost in their craft.

The rates to use the studio are cheap compared to many studios, Malony said. It costs $35 an hour.

Vocalist and songwriter Leanne Trevalyan from Tacoma-based blues and Americana band Junkyard Jane said it’s not only Malony’s “big ears” that bring her band back, but the creative atmosphere his studio facilitates. The studio is warmly lined with wood as opposed to the stale laboratory-like environment Malony said many studios possess, and Trevalyan said it’s worth the drive.

“The atmosphere at his studio is really conducive to creativity,” Trevalyan said. “The band camped out in an RV and tent during our first project together, and the woodsy atmosphere make it a great place to hang out and record.”

Malony wasn’t always a sound engineer. Originally from the Philadelphia area, he was a drummer in numerous bands before his move to Whidbey Island in 1991. After a few squabbles with how one of his band’s end products should sound and be recorded, he decided he wanted more say in the mastered and finished product. He’s never looked back.

“When the digital change happened the studio just kind of evolved under me,” Malony said. “I originally never had intentions of running a studio, but when I got a call from Junkyard Jane, I thought it was an interesting idea.”

Since those early days, Blue Ewe Studios has welcomed bluegrass bands, folky singer-songwriters, an Earth, Wind & Fire cover band, metal bands “from the naval base in Oak Harbor” and even an audiobook by Langley poet David Whyte. Regardless of genre or the equipment used, Malony’s big ears hear it all. Szabo said the studio is set up for a singer, but the metal bands would beg to differ. Either way, Szabo said Malony is a mixture of old school and new school and knows all the equipment in his studio like the back of his hand.

“We’re not talking about a technician, we’re talking about an artist,” Szabo said.

A key to the recording process is reading people, Malony said. It’s half of what he does; he monitors musicians’ energy levels to get the right sound and does what he can to make them feel comfortable. If artists are empty of comfort and enthusiasm, he often sends them home so they can try again the next day. He believes the response from the musician helps dictate the quality of the end product. And reaching that end product is what he loves.

“It’s like painting with sound,” Malony said. “It’s interesting. I feel like when I record, the process is akin to assembling a palette of colors. My job is combining those colors into a sonic picture that’s both unique and pleasing.”