“When in doubt, stay out.”

It turns out that simple catch phrase advertised on the state’s Department of Ecology website about lakes containing neurotoxins has extra relevance with Lone Lake. Though a layer of green “scum” on the surface of the water this past week served as evidence of a toxic algae bloom that forced the lake’s closure on July 19, the water was clear Thursday morning.

But that doesn’t mean you should go for a swim.

“Even if you see the bloom and it dissipates, you can still have neurotoxins,” said Lizbeth Seebacher, a biologist with the Department of Ecology’s Freshwater Algae Control Program. She added that it’s possible wind or cooler weather can reduce blooms, but not the neurotoxins in the water.

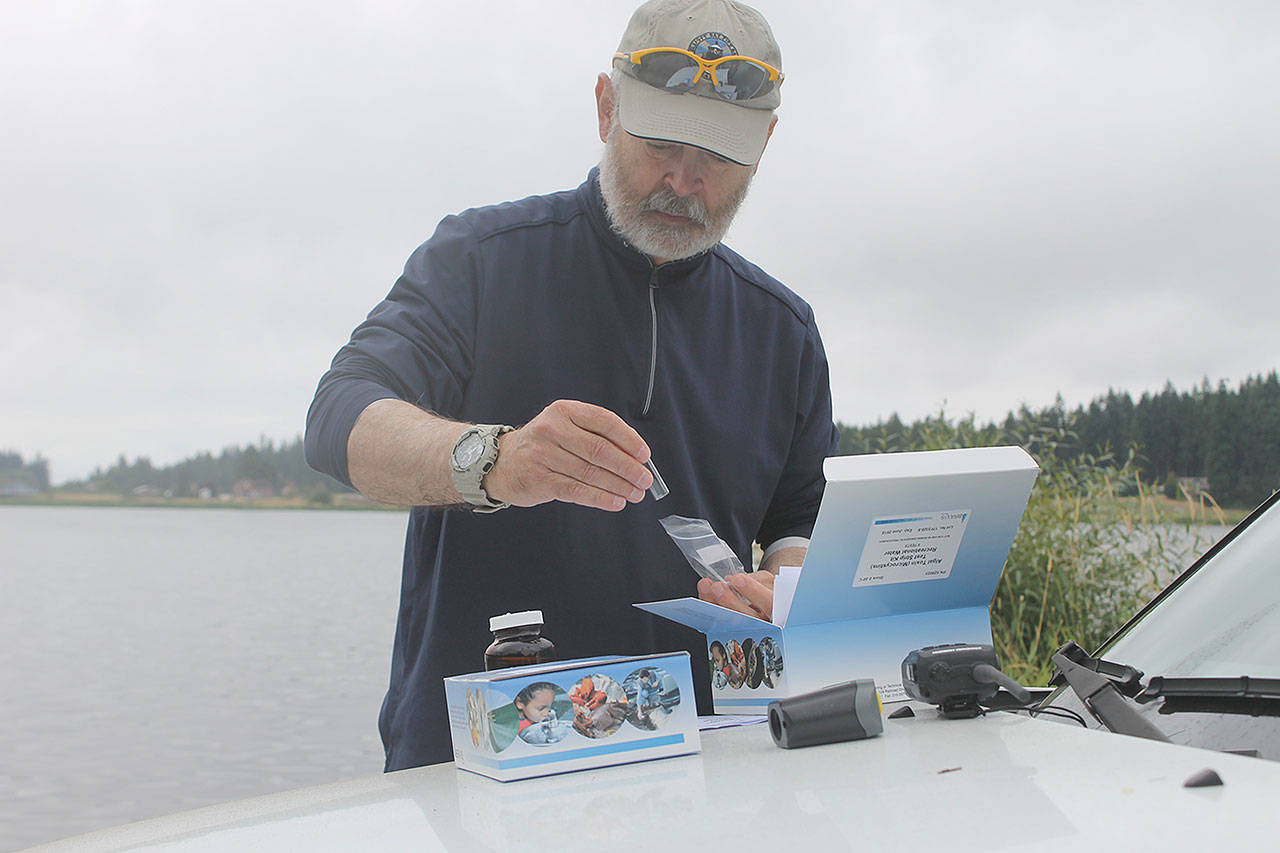

Two separate water sample tests by Clyde Jenkins of the South Whidbey Yacht Club found toxic algae levels to be well over the state recreation limit. A water sample collected on July 20 found 160.59 micrograms per liter of Anatoxin-a, a neurotoxin that can disrupt the link between nerves and muscles and can lead to loss of coordination, convulsions and death by respiratory paralysis. Jenkins conducted another test on Thursday and will send the water samples to a lab in King County for further analysis. His preliminary results showed a decrease in Anatoxin-a levels, but are still above the state recreation limit. Official results are expected on Monday.

Counties are advised by the Department of Health to continue testing the water for signs of toxins until toxic algae levels decrease. If tests show neurotoxin levels are below the recreational limit for two weeks, the lake can be reopened.

It won’t come soon enough for the yacht club, which was forced to cancel a regatta scheduled for this weekend due to the unsafe water conditions, Commodore Bob Rodgers said.

Neurotoxins in Lone Lake are not a new occurrence; toxicity levels were also high in July 2015 and July 2016 according to Washington State Toxic Algae’s website, a freshwater algae bloom monitoring program. A specific cause for the algae bloom is not yet known according to Island County and Whidbey Island Conservation District Officials. Some of the leading theories include high nutrient concentrations, warm temperatures, goose poop and runoff from pastures, roads, lawns and leaky septic systems.

The shallowness of Lone Lake could also be a major factor in the algae bloom and can also help explain why problems appear to be so persistent there. Mark Sytsma, an environmental sciences professor at Portland State University who recently bought a house near the lake, said shallow lakes typically exist in one of two stable states: one with high turbidity and algae growth and no plants or one with abundant plants and clear water. The latter is a better fish habitat and can help stabilize the sediments, but the plants can also interfere with boating and swimming.

Lone Lake’s depth of 17 feet is relatively shallow compared to the 50-60 feet depth of its Bayview counterpart, Goss Lake. Deer Lake is 30-40 feet deep.

Sytsma said Lone Lake is also exposed to more wind than Goss Lake, which causes the displacement of sediments and release of nutrients. Nutrient buildup can lead to low levels of oxygen in a process known as eutrophication. This process manifested itself in the deaths of about 1,000 fish in September, 2016. The problem with the shifting of sediments is also compounded in Lone Lake because plants were eliminated by a combination of herbicide treatment and grass carp. The grass carp, introduced in 2009 by concerned homeowners, were meant to keep Brazilian elodea, a noxious non-native weed, from infesting the lake. But, they’ve since reduced submerged plant communities and contributed to algae blooms. Bow fishermen have begun to reduce the carp population, estimated at about 800, in nighttime hunting missions along the shallow banks.

“Its condition is an algae dominated state, not plant dominated,” Sytsma said. “You could switch it back to plant dominated with fewer algae blooms, but it takes a lot of work to make that happen.”

Island County does not appear to be in a position currently to turn things around at Lone Lake. Jill Wood, Island County Public Health’s environmental health director, said the county lacks the funding to support a blue-green algae problem that can examine the problems surrounding Lone Lake for a sustained period of time. Island County Commissioner Helen Price Johnson said the lake is owned by the state, and the state administers funds for environmental health. She said state lawmakers like Norma Smith, R-Clinton, are aware of the problem. But, she was told that it falls in priority compared to other areas of the state budget such as education funding.

“We would welcome the opportunity to do more, but we need to have the resources to do that,” Price Johnson said.

The county has two programs that monitor water quality, one for saltwater shorelines and the other for freshwater lakes. Island County Environmental Health Specialist Maribeth Crandell said the two programs are BEACH and SWIM. The BEACH program, which receives funding from the Department of Health and Department of Ecology, takes samples from popular swimming beaches like Freeland County Park and Windjammer Park in Oak Harbor in the summertime to monitor water quality. SWIM, funded by the county, conducts monthly tests for e.coli in freshwater lakes across Whidbey Island.

Because of a lack funding, the county relies heavily on the community, such as people like Jenkins, to collect samples and send them to King County where they are analyzed for free.

There is, however, some hope on the horizon. Crandell said the county is discussing the possibility of applying for a Department of Ecology grant in the fall. Similarly, Sytsma said he is working with the Whidbey Island Conservation District to also receive a grant from the Department of Ecology, which would allow “us to better understand the sources of nutrients to the lake and to develop options for improving lake water quality.”