An outdoor sculpture that’s greeted visitors to Whidbey General Hospital in Coupeville since 1970 was demolished several weeks ago.

Officials discovered the sculpture was deteriorating after reviewing a landscaping plan for the front of the hospital, which just changed its name to WhidbeyHealth Medical Center earlier this month, said George Senerth, executive director of Facilities and Plant Engineering.

The hospital is in the midst of a $50-million construction project to build a new 39-bed patient wing. It’s scheduled to be completed next year.

Officials also just unveiled a new sign featuring the hospital’s new name and a directory sign in the vicinity of where the sculpture used to sit.

The new signs had nothing to do with the removal of the sculpture, Senerth said.

“It was a safety issue,” he said. “The brace inside the structure was beginning to rust and rot.”

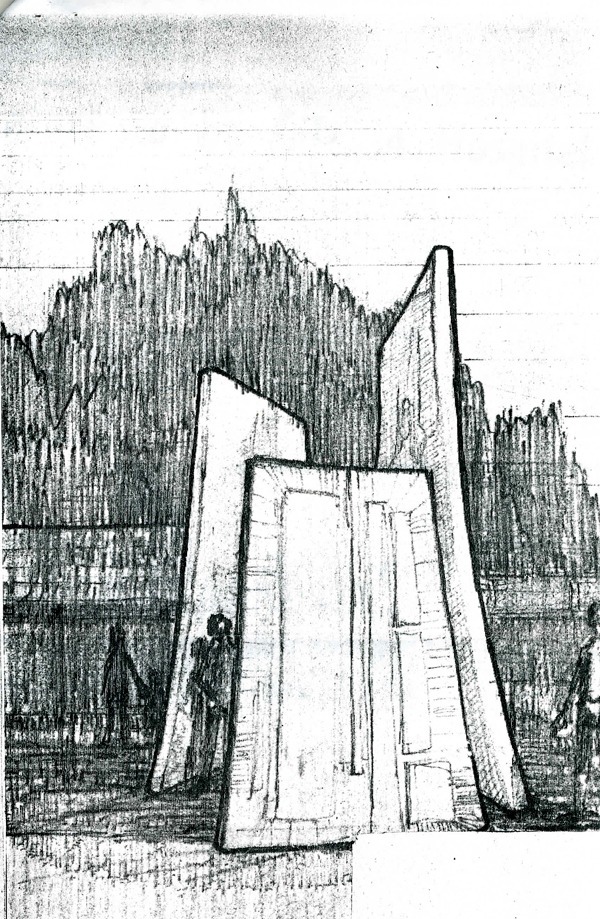

The untitled sand-cast concrete sculpture featured quadrilateral slabs of concrete in relief patterns. Three slabs were set into the ground to form a triangular-shaped open room through which people could walk. A bench was outside.

The sculpture was designed and created by artist Michael Park along with the help of sculptor Charles Talman. In a 1970 article in the Whidbey News-Times, the artist said the sculpture was meant to symbolize “the hopes, concerns and attitudes” of the hospital. Both sculptors volunteered their time to create the piece and the $500 material and installation costs were paid for by donations.

In the 1970 story, Park said he wanted to create a “Stonehenge” quality for the works that he estimated would weigh 12 tons and have a diameter of 8 to 10 feet. The work was similar to a structural method Park used in other pieces he created for parks in Colorado Springs, Colo.

The article described Park at the time as a young man and five-year resident of Whidbey Island who designed and built homes. At the time, Talman was a sculptor stationed at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island.

When Senerth took a closer look at the sculpture last month, he said he saw the outer layer of cement was crumbling and the brace that supports the structure rusted.

Hospital spokesman Keith Mack attempted to locate artist Michael Park or his family to no avail. The hospital doesn’t plan to replace the sculpture with something else, but the new wing does include a budget for artwork inside.

The sculpture was registered with the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Save Outdoor Sculpture program in 1995 by then hospital administrator Doug Bishop. The national program seeks to inventory and protect outdoor sculptures, which the Smithsonian considers an accessible art form and one endangered by vandalism, pollution and neglect.

At the time the sculpture was registered, the Smithsonian listed it as “well maintained.”

Bishop said he was approached by someone from the Smithsonian in 1995, who happened to be looking at another piece of outdoor artwork in Langley. The woman said she was driving by the hospital when she saw the sculpture.

“She thought it was a significant piece of art and suggested we register it,” he said.

The structure was originally located closer to the entrance of the hospital. When the hospital expanded about 15 years ago, the piece was moved closer to the road, he said.

When Sept. 11 happened, local residents used the sculpture as a makeshift community memorial, placing candles and flowers at its base.

“I happened to be driving by the other day and noticed it was gone,” Bishop said.

“I was sorry to see it go.”