Whidbey folks know him as Herr Drosselmeyer in Whidbey Island Dance Theatre’s annual production of “The Nutcracker.”

But to the folks down in Haiti, Lars Larson deals in much more than toy nutcrackers. Down there, he practices the magic of helping people to survive.

The Langley resident’s connection to Haiti began in 1998 when a small team of physical therapists, medical doctors and other rehabilitation support staff from Salt Lake City, Utah went blindly and with big hearts to Haiti to provide rehabilitation care for the disabled persons of the poverty stricken Caribbean island.

A friend of a friend happened to mention the group to Larson, a builder, who went along to help with renovations for a rehab clinic, a guest house for the medical staff and a prosthetic and orthotic device service center.

Healing Hands for Haiti International is now a well-established nonprofit, non-governmental institution, and has been growing ever since. It provides quality physical rehabilitation services and independence to Haitians with disabilities.

“There’s always a need,” said Larson, who usually starts “The Nutcracker” rehearsals right after his September visits to Haiti. “Last time I was there I did four roofs.”

He’s been a frequent visitor, and some years he would return more than once for two to four weeks at a time. Such was the case one year ago today, after the devastating Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake destroyed all but two of the eight buildings the organization had managed to build over the course of 12 years. In one fell swoop, Haiti turned from bad to worse.

After the earthquake hit, Healing Hands chartered a flight for a dozen North Americans to fly to Haiti.

The airport was chaotic due to road closures and was flooded with humanitarians who were eager to help, Larson said, but who were not able travel to any of the sites where they were needed. The scene was indicative of a problem that often plagues disaster sites: how to help when infrastructure no longer exists.

Larson managed to get out of the airport with the Healing Hands crew.

“Healing Hands was there for a month in a tent,” Larson said.

Their work included wound care management, counseling, physical therapy and referring and transporting several acute patients to Haiti’s central hospital and Medishare field hospitals. They also made visits to orphanages.

“The first day we had 260 people visit the tent and 150 people every day after that,” he said.

The logistics of helping victims of a disaster is the trickiest part of providing aid, Larson said.

“It was really back to basics for us, with no running water and no electricity,” he said.

Larson used his builder’s ingenuity to do what he could and make himself useful to the doctors and staff at the makeshift medical tent.

“I never saw nurses so happy as when I set up a makeshift shower for them with some hose and other found materials I scrounged from what looked like a post-apocalyptic place,” Larson said.

One of the buildings used as a storage spot for Healing Hands was damaged badly and remained basically off-limits to the team. But Larson told the rest that he was the one without a family and only he should go in to rescue food and supplies.

“I told everybody that I didn’t want anybody going into that building but me.”

He’d run in, grab what they needed and run out.

“Then I’d catch my breath, take a moment and then run back in,” he said.

But even in the midst of disaster and tragedy, Larson said the Haitian people wear their hopefulness like a badge. T-shirts printed with the words, “Haiti will survive” and “Haiti Forever” are some of the most popular, and most of the people, Larson said, don’t have two cents to rub together and yet they still retain their sense of humor and good nature.

“The stress, the noise, the pollution that these people have in their daily lives, even before the earthquake … we were there for three years in a row before I even saw a garbage truck,” Larson said. “Their resilience is amazing to me.”

Presently, the physical rehabilitation facility in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s largest city, is being rebuilt in partnership with other non-governmental organizations such as Project Medishare, Newman’s Own Foundation and Handicap International and is due to open by the end of 2011. The facility will be managed by Healing Hands for Haiti International.

With all the work that he’s done, Larson still sees a never-ending need in Haiti, especially after the earthquake.

“There’s a real frustration, because it doesn’t seem like we’re doing anything down there. But I think we’re helping to change individuals’ lives. I know they’re changing mine,” Larson said.

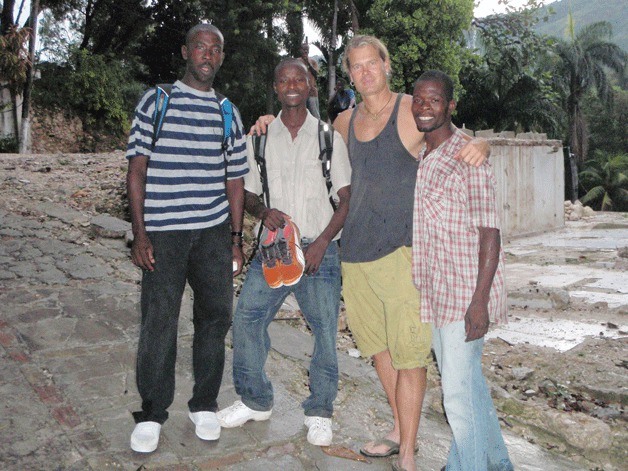

Meanwhile, Larson, back from his most recent trip in September where he left his shoes behind for one of his Haitian friends, continues to keep his island friends on his mind even while he enjoys the comforts of home.

“All I want to do when I get home is eat some American food and kiss my garbage man,” Larson said.

“But I see how much I take things for granted,” he continued. “Anytime I want to complain about something, I wait and think about it.

“I’m a pretty lucky guy,” he added.

To find out more about Healing Hands for Haiti International, click here.