Friends and family recently shared their memories of the man known as “Gentlemen Jack,” and people from Whidbey Island and beyond will mark the passing of the former congressman at a memorial service today in Langley.

Pioneer stock

The Metcalf family’s arrival on Whidbey has become part of local lore.

Jack’s father, John, had bought a beach shack on Camano Island for $10, his wife Norma Metcalf recalled. A commercial fisherman, he had bought 100 acres on Whidbey for $5,000 and decided to move his family, and his home, across Saratoga Passage.

“He put it on rollers and rolled it down to the water, and then towed it with his fishing boat, across just around the point here,” she said, motioning across Saratoga Passage. “Winched it up, put a bulkhead in front of it, and they were home.”

“He brought the cow over the same way, on a raft. That cow got off in knee-deep water and waded ashore.”

Jack Metcalf, who was born in Marysville in 1927, was 6 months old at the time.

Metcalf would later build the Log Castle Bed and Breakfast on his family’s homestead from trees that were logged from the land.

High school sweethearts

Norma met Jack at Langley High School — he was a junior, and she was a freshman — after he got hurt playing football.

“And as they carried him off the field, I happened to be standing right next to his girlfriend. And she was in tears, and crying, and I thought, how dumb. He hurt his knee, big deal. I thought that was one of the stupidest things I had seen. That was my first impression of Jack.”

He later sent her a note asking for a date to the Valentine’s Day dance.

Norma, however, thought the note was a phony and tore it up.

“A few days later Jack came by and asked me why I wouldn’t answer his note. ‘You wrote that? Oh,’” Norma recalled with a laugh.

Her father wouldn’t let her go to the dance.

“I was 14,” she said, “and I knew I was going to be an old maid forever and live with my parents.”

Her parents later relented, and drove Norma to the dance.

“That first night, I realized he was a terrible dancer. He didn’t like dancing; he never did. He really did try, all the way through our marriage,” she said.

Sharing knowledge

A love of sports led him to coaching, which led to teaching.

He would spend 30 years in the classroom; 29 years in the Everett School District.

Dick Haines was a student in Metcalf’s sophomore history class in 1974.

“He was fantastic; he was an excellent teacher. We always had a good time in the class,” Haines said.

He recalled the time Metcalf brought a golden retriever puppy to class the day before Thanksgiving break. Metcalf told the students he was going to take it to the animal shelter in the hope that someone would adopt it.

Haines took the dog home instead, and he recalled how Luke the dog became a part of the family through Haines’ time in school, a marriage and a couple kids. The dog didn’t look much like a golden retriever, however.

“I think he was a mix between a miniature poodle and a golden retriever. I always gave Jack a hard time about it,” he said.

Metcalf’s father was a commercial fisherman, and Jack could often be found trying to make a few dollars himself from the bounty of Puget Sound.

Jack’s daughter Lea recalled how he fished during college.

“Before he would go to school he would take his dad’s boat, at midnight or whatever, and go across and fish with a net, and do a haul of commercial fishing… and get back in time to get to school.”

“He did that when we were married, too,” Norma added.

“He would go and fish all night, then I would run the fish to Seattle, and with two little kids, to sell to the Japanese.”

“He’d teach all day, and then he’d come back and he’d fish another night, and teach another day. And he’d grab a little sleep on the boat, an hour here, an hour there.”

During the first half of his career, Metcalf taught algebra.

“He always said it was a paid vacation. He loved teaching algebra,” Norma said.

He switched to history when a new math program was launched that Metcalf didn’t like. “He said he just couldn’t lead the kids down a primrose path,” she said.

A political mind emerges

Metcalf was intensely interested in national world affairs, and kept a close eye on Olympia. It often led to spirited discussions that Metcalf would start in the teacher’s lounge at North Junior High School in Everett.

“He was in the faculty room once, and he was bellyaching and griping and making the teachers mad…and one of his friends spoke up. She said, ‘Jack, you’re always in here griping and complaining about those guys. Why don’t you run?” Norma recalled.

“And the thought had never occurred to him. He thought you had to be well known, and wealthy, and he was neither.

“The thought just grabbed him: ‘I wonder if I could.’”

Metcalf joined the Republican party, starting out as a precinct committeeman before becoming the secretary for the Snohomish County Republican party.

He lost his first race, however, by 188 votes.

“He always said, too, that every politician should lose at least once. They need to know what that’s like,” Norma said.

He didn’t give up, though. Metcalf was elected to the state House of Representatives and served from 1961 through 1964, representing the 38th District.

He later served as a state senator, representing the 21st District from 1967-1975 and the 10th District from 1981-1993.

Snohomish County Councilman Gary Nelson first met Metcalf in 1964, when he was running for the state house.

“It was the first time I ever went doorbelling with somebody where you handed out pumpkins,” Nelson said.

Metcalf had grown pumpkins, and had branded his name on the side of each gourd.

“When he came and picked me up that day in his pick-up truck I thought, ‘This has got to be the nuttiest thing I ever heard of,” Nelson recalled.

Years later, when Nelson was running again in 1972, he knocked on some familiar doors in the district.

“People said, ‘I remember you, but where are the pumpkins?” Nelson recalled with a laugh.

They later served together in the Senate. Metcalf didn’t let partisanship get in the way of friendship.

“You just cannot function if everybody is always angry at each other. And Jack was really a good guy for that. He was always good natured; he was a gentleman beyond belief.”

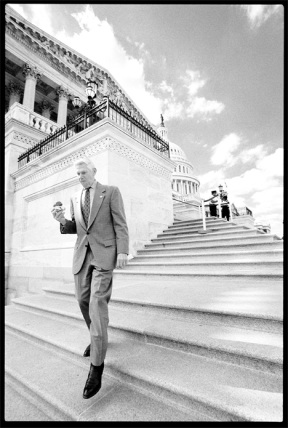

Making a mark in Washington

He made three unsuccessful bids for Congress in 1968, 1974 and 1992 before winning election during the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994.

State Rep. Chris Strow, who served for five years as an aide to Metcalf in Congress, said the congressman had political currency that helped him work with members of both parties.

“It was the integrity of his word,” Strow said.

“It’s an interesting legacy. He meant a lot to a lot of different groups. In many ways to conservatives he was almost the Pacific Northwest’s Ronald Reagan; he was a voice for Reagan and Goldwater conservatism at a time when there were few up here,” Strow said.

“To another group, he was a great conservationist. He truly believed in the protection of our natural resources and leaving that to future generations,” Strow said. “For another group of people, he was a politician of almost a different age.”

“He was truly a decent man who cared about the little guy,” Strow added.

Nelson agreed.

“There were times when he made a few people a little bit frustrated,” Nelson said.

“He helped a lot of unions in the course of his being in the Legislature; buyouts of companies, or healthcare, or bargaining criteria, strikes. He really had a strong feeling of making sure that working men and women had a fair opportunity to not only obtain jobs, but to retain jobs,” he said.

Strow said he told people who thought they had Metcalf pigeonholed that they were missing the mark.

“He could be a right wing nut, a left wing nut and a practical centrist all in one day,” he said.

Metcalf, as well, would rarely show anger. One time he came close, Strow said, was when his wife complained that it was taking him too long to get the authorities to take action and remove a dead whale that washed ashore next to the Metcalf’s bed-and-breakfast outside Langley.

Strow laughed when recalling Norma’s threat to call Sen. Patty Murray, a Democrat. “I know Patty will get this done.”

“Jack was…a little chagrined more than anything else,” Strow said.

Even so, he spoke forcefully on issues he cared about.

“Jack fought for what he believed in, but he did not hold grudges,” said Lew Moore, Metcalf’s chief of staff for almost his entire time in Congress.

“He could separate people from what they believed; he had a lot of friendships, and a lot of folks’ respect from across the aisle,” Moore said.

Metcalf had political currency that helped him work with members of both parties, Strow said.

“It was the integrity of his word,” Strow said.

State Rep. Brian Sullivan, D-21st District, has known the Metcalf family since he was 9 and they lived in Mukilteo. Norma was the school secretary at his junior high school, and he went to school through his sophomore year with daughter Bev.

“They grew up three or four houses up the goat trail from us,” he said.

Sullivan, who was on the staff of state Sen. Larry Vognild in the early 1980s, recalled when he crossed paths with Jack Metcalf again in the state capital.

Sullivan recalled the impassioned speech Metcalf gave against the establishment of the state lottery system.

“Jack gave a great speech on the importance of family and the decimation of society if we passed this gambling act into law,” Sullivan said. “It was a very great speech.”

He laughed when he recalled later that night, looking for Sen. Vognild to deliver some papers. Somebody suggested checking the Senate cafeteria, and there he found the Vognild playing a gentleman’s game of poker with Metcalf and other senators.

“Regardless of the issue, they were all great friends. They respected each other,” Sullivan said.

“You could have great disagreements, you could say anything you wanted on the floor of the senate, and you would come out of it and your greatest opponent in the debate is your best friend,” he said.

A political maverick at work

Metcalf served as a 2nd District Congressman for three terms before retiring in 2001.

He earned a reputation as a maverick. He was the lone member of Washington’s delegation to vote in 2000 against a bill that granted permanent normal trade relations with China. He also battled the Makah Tribe’s attempts to restart whaling off the Washington coast, and led efforts to improve natural resource and fisheries management and environmental protection.

He worked tirelessly, too, on behalf of the men and women in uniform. He supported investigations of the causes of illnesses faced by veterans of the Gulf War, and increased funding for military family assistance and homeless veterans’ programs.

In state government or in the nation’s capital, Metcalf left a well-deserved reputation as a gentlemen.

“He found in Olympia as he did in D.C., Jack always had a statement for everybody, even if they were twisting a knife in his back. It was always, ‘He’s a good guy,’” Norma recalled.

“He found a lot of good guys, in both parties.” she said.

Metcalf was also a firm believer in term limits in Congress, noted Nelson, the Snohomish County councilman. Metcalf had promised he would step down after three terms, and he did.

“He said if you can’t get anything done in three terms, it’s your own fault,” Nelson said.

The family man

A little more than five years ago, Metcalf was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. He was admitted to HomePlace, an Alzheimer’s care facility in Oak Harbor, in late December and died from complications of the disease on March 15, surrounded by his family. He was 79.

Despite his success in Olympia and Congress, his family said it never went to his head.

“He was the guy who chopped wood for the wood stove,” said Lea Metcalf, one of his four daughters. “My friends from college would all come over…they would be so surprised.”

Norma, his wife of 59 years, said she learned early on how to keep him grounded.

“I always had him empty the garbage,” she said. “These guys, when they are in Olympia, they get the door opened for them — ‘Let me get that door for you, sir.’ They always build them up, put them on this pedestal.

“So the first thing when he came in the house when he got home, I’d say, ‘Oh Jack, the garbage needs to be emptied.’ It brings you back to reality if you empty the garbage.”

It was a secret she’d share when the couple went to Washington. Norma recalled how, at her first congressional wives Bible study meeting, the topic came up. She shared her tip, only to hear it repeated by another congressman’s wife during another Bible study meeting when Metcalf was serving his third term in Congress.

“I made my impact!” she said, notching a mark in the air with her finger.

Beyond the immeasurable love for his family, Metcalf loved to laugh. Norma recalled the time in Olympia that he took an intern, and a roll of strong nylon fish line, to the top of the rotunda and used the line to lasso the chain on the 2-ton chandelier that hangs from the capitol dome.

Once they caught the chain, Metcalf began to pull the line tight.

“He got that thing swinging in a 20-foot arc. He pulled in the nylon line and put it in his pocket and went down to breakfast,” Norma said, recalling how the media became fascinated with the strangely swinging chandelier and speculated that there may have been an earthquake in the capital.

“Then 10 years later, on April 1, that chandelier swung again. Can you imagine that?” Norma asked with a laugh.