By DANIEL GOLDSMITH

Thirty days since the storm began, cleanup crews are loading the sheet rock, insulation, appliances, furniture and personal possessions that are piled along the arterials of rural Texas. It gives the appearance that things are returning to normal. It has been a month of gut-wrenching relentless work, trying to stay ahead of the mold that follows a flood. Materials are in short supply, contractors are behind, not everybody is as honest as they appear and most folks are bone tired. Daily national news has turned away from the disaster and the memories of 100,000 families molder at the curb. Sorrow permeates the air of the abandoned subdivision. Meantime the residents do the best they can to clean up, maintain and move on.

On Sept. 2, we loaded a 16-foot utility trailer at Bush Point with donations. Neighbor Bill says, “Why in the hell would you do that?” I’ve asked that question before. Mr. South Whidbey mentor Rocco Gianni sighs, “Let your conscience guide you.” Demand for disaster housing inspectors is huge and I’m trained. Seven days, two breakdowns and 1,800 miles later, I’m at the Port Arthur distribution center. One hundred percent of the city’s residents were flooded and utilities are just coming back. Manned by the National Guard and coordinated by the United Board of Missions, it swarms with vehicles unloading, transferring and loading.

I’m assigned to Orange County, which is east of Houston and home to oil fields and refineries. It’s rural, flat and swamped. The hotels in Beaumont are over-filled with displaced homeowners, refinery workers, contractors and clean-up crews. I need a place to sleep other than the utility trailer. I pull in to the Americas Best Hotel along Interstate 10, a Mediterranean style two story, pale yellow structure with bright blue trim. Jake, the east Indian proprietor, is helpful. I tell him why I am here. “Today is your lucky day.” He has an apartment, used for families, tucked in above the storage and laundry. It’s luxurious compared to the rooms they offer. I’m in. I can go to work.

Housing inspections take 70-80 hours a week; at 70 years old, the work wears on me differently. Forty to 50 families a week; by random sample, a slice of America — rich, poor, big families, small, working or retired. “I never thought I would see this in my lifetime” is a common response. Fifty-three inches of rain, a 500 years storm, swamps everything in the vicinity. Some applicants have stripped their homes down to the studs, others are waiting, uncertain what to do next. Disaster relief is just that, not near enough to make them whole. Most are buoyed by the thought of getting a stipend to begin to rebuild and are appreciative. That’s thanks enough for me.

I return at sunset, after a full day, smelling of Pine-Sol, Clorox and mold. I’ve forgotten the key in my “apartment.” Jake is not at the desk but returns in a minute. “Pardon me,” he says, “we Hindus pray twice a day, in the morning and in the evening.” I’m thankful for the safe place to do my paperwork, make my calls, to sleep and eat and from which to launch each day. Doubly blessed and thankful for the place I call home and those who support me. Maybe Jake’s onto something. Doubling up on prayer in a disaster zone makes sense. Prayers of thanks each day.

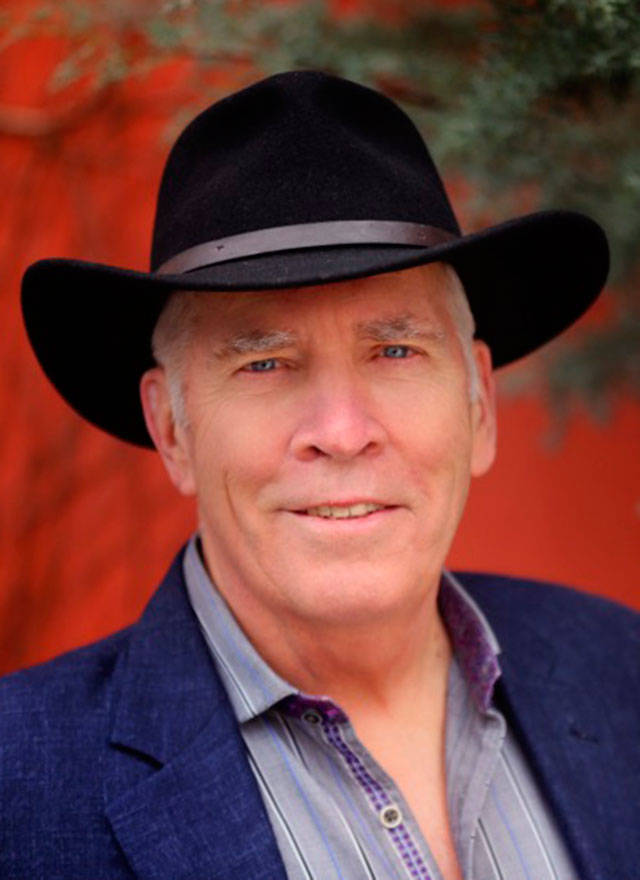

Editor’s note: Freeland resident Daniel Goldsmith is a real estate broker and disaster housing inspector when needed. This is his seventh deployment since Katrina.