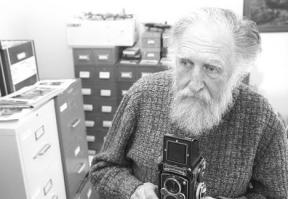

When looking into Victor D. Seely’s eyes, so softened by age but still carrying a twinkle, you are looking into aviation history. Many people are unaware of this soft-spoken 75-year-old Clinton resident — a full-bearded slender man known simply as Vic, as husband to Joy, father of three, and grandfather of four. You might have seen him and his wife at Mike’s Place, where they eat breakfast every morning, or another local joint where they more often than not also catch lunch.

He slips under the radar like so many of the aircraft he adores, but unbeknownst to most, Vic Seely has one of the largest private aviation photography and records collections in the Northwest. He is also one of the most prolific minds in the world when it comes to machines that fly.

At over 55,000 photos and still counting and collecting, Seely remains modest over his endeavors.

“Well I can’t compete with the Smithsonian, can I?,” he said.

His collection overflows into every room of his house. The basement houses a number of his larger filing cabinets. Hallways are lined with shelves filled with books about airplanes, aviation, and the armed forces, printed in about every language. The upper floor of his home had to be reinforced to support some of the more than 5,600 pounds of files in his upstairs office. He even uses one of the bathrooms for storage, with all sorts of maps kept within.

If it’s not photos, maps, charts, stats, engineering specs or newspaper clippings, it’s trinkets and model planes that dot every nook and cranny of the Seely home. Even Molly, the couple’s fluffy black cat, has to share her favorite room and curl up with the aviation materials.

Seely’s story is one that is bred from aviation history.

As a 10-year-old boy in 1938, Seely decided he wanted to work for Boeing. That year, he saw the company’s first big flying boat, the Boeing 314 Clipper, roll out. Cementing his goal was a walk with his father down the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga, a memory Seely said still remains strong.

Throughout his adolescence, he did everything he could to pursue that dream. His father, John A. Seely, often took him to Sea-Tac Airport to watch planes fly in and out. He also showed young Vic diesel engines he helped build while a machinist at Washington Ironworks.

It all helped mold Seely. He found a love for science and even skipped three grades before reaching high school.

When Seely attended West Seattle High School 1943-45, he, like many other students during wartime, helped make model planes the Navy used to train its pilots. The tiny replicas helped pilots learn which aircraft were friend and which were foe. Seely began collecting Spotter’s Guides, and added exact replica details to the often plain templates offered by the Navy.

“They were awfully void of details, and the planes needed to be as close to what they’d see as possible,” he said.

He studied the Spotter’s Guides and soon wanted to know about every plane ever made.

For a class project in his industrial arts class, he chose to design airplane engine parts, and he took the plans to Boeing to inquire about a job.

Three days later and six years after determining his dream, he was sitting at a drafting table in the Red Barn as a member of Boeing’s engineering department. The 16-year-old was a tracer, working full-time at Boeing drawing in india ink over pencil sketches the engineering plans for the B-17 “Flying Fortress.”

“War was on and Boeing needed help,” he said. “Plus it helped that I played pinochle with my bosses and always let them win.”

Vic built his photo collection every payday when at lunch time he’d gobbled up his sandwich and run to the public relations office to buy a handful of photos.

In 1948, Boeing gave Seely time off to attend the University of Washington, where he studied physics and nuclear physics. His college education was cut short when in his third year he was drafted by the Army for the Korean War.

Despite no medical background, he became an X-ray technician for the 320th General Hospital. He soon became in charge of photo chronicles for the unit and took his darkroom with him during his two year tour.

After the war, he returned to Boeing. In 1961 William M. Allen, Boeing CEO at the time, started a five-member history committee. It’s objective was to educate the public on the history of Boeing Corporation and it’s role in the history of aviation. He appointed Seely to one of the seats.

On the history committee, Seely was able to further feed his photo collection, as it was now part of his job to gather photos, write articles, and collect all the aircraft knowledge he loved.

At the same time, Seely work his way up to the position of design specialist with the engineering department, from which he eventually retired after 36 years. But his role with Boeing wasn’t over.

He one of the founders of the Seattle Museum of Flight, having worked on the project since museum concept planning and through fund-raising efforts to help make the museum possible. Seely became the first curator of the museum, holding the position until 1992.

He remains as a constant advisor for museum staff.

“People call all the time to pick his brain,” said Rosemarie Gran, telecommunications manager for the Museum of Flight. “He just knows so much about just about every plane made, and to this day people call looking for Vic Seely.”

Currently, when not building his collection, Seely has a number of side projects. At one time he had his own mail order model plane business. He appraises collections of aviation photos, materials and the like, and has even appraised the collection of William Lear. He researches aircraft, Navy bases, and sends off photo prints requested by people from around the world. He contributes writing to other authors’ books, and has even completed a volume for a plane enthusiast by the request of his widow. For his own unfinished book — about every flying boat ever made — he already has 3,000 pages at the paste up stage.

As if that wasn’t enough, he is once again helping a fledgling flight museum. He is a member of the PBY Memorial Association, a group that is trying to preserve the legacy of the PBY Catalina and the Oak Harbor seaplane base from which the seaplane operated during the 1940s. To help the effort he is supplying pictures, data and history about the PBY, NAS Whidbey and the Navy to help get the memorial off the ground.

For more decades than he can count, Seely has been a member of the International Aircraft Photo Exchange. His long-time mentors Peter M. Bowers and Gordy Williams, both recently deceased, were also members.

In recent years he’s had to make a move with the technological times. He is currently scanning and logging — quickly — his photos onto computer storage media.

“You’ve gotta rush when you’re 75 like me,” he said.

He keeps record of everything, and only threw away some photos to make space when he shipped off to Korea — an act he has since regretted.

“I could never get back some of the photos I had at the time,” he said.

But he’s holding onto everything else.

“If this all burned it would make no difference to 90 percent of the population,” he said. “But the people who make it all worth it are those who have done their part during war time, during peace time, building these planes, flying them and working with them on a daily basis.”

Looking at his other photo collection tendencies, one can see the life history of Vic Seely. His years at Boeing are so tightly intertwined with his photos of planes. He adores mountains — no doubt influenced by his tours through Europe’s lovely ranges while in the Army. And an ironworking father contributed to Vic’s appreciation for locomotives and a love for the Vashon ferry boat, as his father helped build the engine of the latter.

In Vic Seely’s eyes is aviation’s past. Through his knowledge grows aviation’s future.