Starfish are one of Charlie Seablom’s favorite aquatic animals to discover.

The pisaster starfish, known officially as a “seastar,” has the traditional five limbs and comes in a wide variety of colors. The orange-colored sunflower sea star grows to be far bigger, can have up to 24 legs and can “run” quite quickly.

But as a volunteer for the Island County Beachwatchers organization since 1993, Seablom has started to see changes in his favorite sea creature.

“The ones I’m seeing, a very large percentage appear to be diseased,” Seablom said.

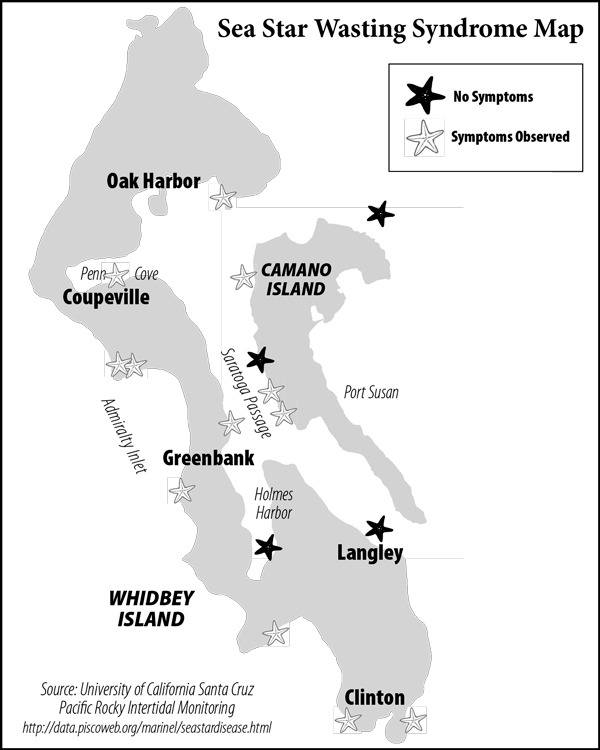

Over the last year, a number of dying starfish have been reported off the coasts of Whidbey and Camano islands.

This year is the first year Seablom has seen any of the “wasted” sea stars on Whidbey. But he’s been on the lookout since the first symptoms were reported in June 2013 by researchers from Olympic National Park. Since then, sea stars along much of the North American Pacific coast are dying in great numbers from this mysterious “star wasting” syndrome.

This year is the first year Seablom has seen any of the “wasted” sea stars on Whidbey. But he’s been on the lookout since the first symptoms were reported in June 2013 by researchers from Olympic National Park. Since then, sea stars along much of the North American Pacific coast are dying in great numbers from this mysterious “star wasting” syndrome.

“It’s real sad to see animals die off like that,” Seablom said. “I just hope they find the cause and then maybe a cure before they’re all gone.”

Central Whidbey resident Barbara Bennett, program coordinator for the Beach Watchers, said Island County monitors 30 beach locations across Whidbey and Camano islands and is seeing the seastar wasting mainly on the west coasts.

The symptoms Beach Watchers are reporting include lesions on the seastar’s skin followed by decay of tissue, which leads to its body falling apart and death, according to sources at the University of California Santa Cruz.

The university is taking the lead on seastar wasting tracking on the west coast and locals who sight starfish can report them on the school’s Pacific Rocky Intertidal Monitoring web page.

A deflated appearance can precede these signs of the disease and the progression of the wasting disease can be rapid, leading to death within a few days, according to the university.

Researchers believe the phenomenon is caused by a bacteria or a virus, but testing is still being done.

“The scientists are really stumped,” Bennett said. “We’re hearing people say there’s piles of them. Here we’re not seeing the usual population.”

Bennett said the disease interferes with their hydraulic system and in some cases, limbs have been known to fall off and crawl away on their own.

“It’s kind of an alien thing,” Bennett said.

The disease is also highly contagious and residents are discouraged from touching or moving any of the sea stars.

There have been recorded drop-offs in sea star populations in the past, Bennett said, but it’s never been in such a broad area or as “expansive” in the dying.

Bennett opined that the star wasting could be happening because other things are off balance, such as temperature or chemistry of the ocean. It may also be the result of pollution or climate change.

Rapid funding from Washington Sea Grant and National Science Foundation is being used to survey intertidal and near-shore areas of the coastline where researchers say there is little to no information about sea star populations, according to University of California Santa Cruz sources.

Recently surveyed areas include Whidbey Island, the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula, from Salt Creek to Port Townsend and the mainland coast near Bellingham.

Additional surveys are being done in the San Juan Islands by researchers at Friday Harbor Labs.

For more information or to report a sea star sighting, visit www.eeb.ucsc.edu/pacificrockyintertidal/data-products/sea-star-wasting/.