LIHI comes better prepared for community meeting

Published 1:30 am Friday, September 26, 2025

Despite ample outcry from the community, a Low Income Housing Institute project on South Whidbey has thus far yielded positive outcomes.

During an informational meeting Thursday evening in Freeland, LIHI staff came better prepared to answer difficult questions about the Harbor Inn project, which is a few years in the making. Island County commissioners voted in 2022 to provide $1.5 million in matching funds to LIHI for the purchase of the motel in Freeland.

After being awarded the funds for the project, LIHI faced a lawsuit from a newly formed limited liability company, Freeland Concerned Citizens – which later dismissed the lawsuit – and a tough crowd at a community meeting in 2023 that didn’t let LIHI representatives off easy.

The organization plans to split the Harbor Inn’s motel rooms between 11 units of permanent supportive housing and nine units of short-term shelter for Island County residents in danger of becoming homeless. So far, only the latter is available; permitting is still ongoing for permanent supportive housing.

LIHI Director of Supportive Services Victoria Kent said the Harbor Inn has served 42 households, with 30 of those experiencing successful exits to housing. The vast majority of these exits have been to housing on Whidbey or to other LIHI housing. Many of the organization’s properties are located on the mainland. In some cases, people went to transitional housing or reconnected with family members.

Staff also said 911 calls at the site have significantly decreased compared to when it was a motel, a claim which Island County Commissioner Melanie Bacon, who was in attendance, supported. Bacon said Sheriff Rick Felici had told her the same thing. In addition, Nick Walsh, fire chief for South Whidbey Fire/EMS, said very few calls have come in from what he recalled.

An alliance of churches in the area – consisting of St. Augustine’s in-the-Woods Episcopal Church, Trinity Lutheran Church, Langley United Methodist Church and Island Church – has been providing people with welcome baskets, transportation and meals.

“One comment was from one of the clients that we heard … was, ‘No one’s ever done anything that nice for me,’” John Porter, a representative of St. Augustine’s, said.

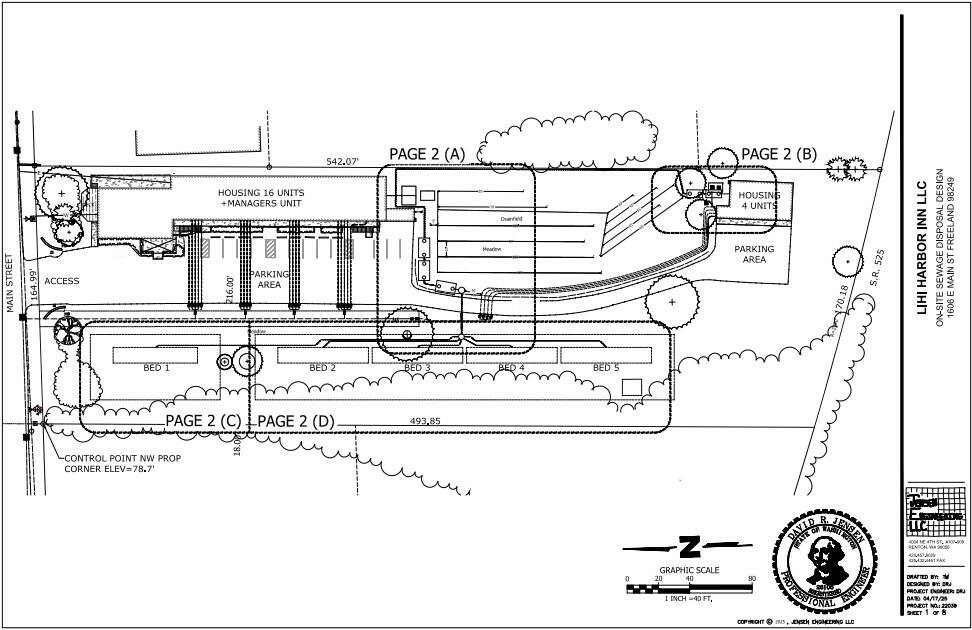

Next steps for the project include the addition of water meters to each individual unit, a septic system upgrade and phased rehabilitation of the rooms. Demian Minjarez with SMR Architects explained that changes are being made only to the interior, not the exterior of the building. Currently, a land use permit is under review and a wetland survey is in progress.

The project’s total budget is $6.1 million, with approximately $1.7 million earmarked for construction costs, Director of Housing Development John Torrence said.

Attendees in the audience asked about the length of stay at the short-term shelter and if drug use is allowed. LIHI staff responded that the temporary guests can stay up to 28 days with the option to stay longer if they aren’t able to secure permanent housing or if things don’t work out in time. For example, a person might not have a birth certificate and obtaining a copy from the state they were born in could take longer than a month. Guests also sign a code of conduct that prohibits drug use.

A former Harbor Inn guest who was at the meeting testified to the rigidity of this no tolerance policy, saying a friend “messed up” and was kicked out of housing after just two days.

Kent encouraged people to remember that drug addiction is a disease that needs to be treated, but people can’t be forced to seek treatment.

“So I just caution having the perception that drug and alcohol use is allowed or condoned in our properties,” she said. “It’s more that we want to support that individual in making good choices, and refer them to specific agencies if they want.”

Once permanent supportive housing is in place at the Harbor Inn, residents who make 30% of area median income will sign a six-month lease. The next step will be for LIHI to turn in a building permit for review for change of use and improvements at the site, according to Island County Planning Director Jonathan Lange.

Expressing concern for the vulnerable individuals currently living in the shelter, one attendee with experience in the construction industry repeatedly asked about LIHI’s plans to mitigate asbestos, citing U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development regulations. LIHI representatives said they are deciding whether to remove or encapsulate asbestos, and assured him it was not in areas where it would be disturbed and present a risk, but this response did little to satisfy the commenter.

In an email Friday morning, Chief Strategy Officer Jon Grant said a state public health inspector visited the site twice prior to opening as a shelter.

“We fixed a few issues the building had because of its age and general lack of upkeep by the previous owner,” Grant wrote. “Repair work included reinforcing the stairs and replacing outdated water heaters. None of this work would have disturbed asbestos in the ceiling or walls. This was all done well before clients were onsite, and we are cleared to safely have clients live in our shelter.”

At the meeting’s conclusion, Bacon said she was grateful for the community gathering and hoped there would be more to come in the future.

“There’s no permanent supportive housing anywhere on the island,” she said. “And so we are very, very excited to have at least these 10 units coming aboard one of these days.”